In search of Timothy Treadwell (Conclusions)

I've titled all of these pieces "In search of Timothy Treadwell, but so far I have said little to nothing about the man and my thoughts on him. Over the last couple of weeks I have read two books about him (The Grizzly Maze by Nick Jans and Treadwell's own book Among Grizzlies), have watched the movie Grizzly Man, have spent several days camping/hiking in the same place, have seen some of the same bears and have spoken to at least one person who knew him personally. I realize that this by no means makes me an expert on the man, but it's probably fair to say that this experience (along with my generally high level of interaction with the natural world) give me a greater-than-average insight.

Treadwell was not crazy

Contrary to the portrayal of his character in Grizzly Man, it is my firm belief that Treadwell was not crazy. No doubt that the guy had had a rough life and his desire to tell a good story and seek attention led him to not always be one hundred percent factual. But his approach with the bears was remarkably grounded in reality and his ability to interpret bear behavior (at least in coastal southwest Alaska) was spot on and rivaled by few others. His approach was--shall we say--"unconventional" which made him the type of man which many people (Alaskans, scientists, xenophobes) love to hate, but that shouldn't detract from his indisputable skills and abilities such as being able to identify individual bears from hundreds of meters away, surviving the harsh camping environment of Alaska for nearly two decades of summers (where it can rain for days and days straight), and being an animated and enthusiastic liaison to sheltered suburbanites in Southern California who would otherwise have little to no connection with natural ecosystems. Near as I can tell Timothy Treadwell was undoubtedly a complex character, typically misunderstood, sometimes selfish, but usually well-intentioned. He may have come across as being certifiably insane (certainly how I viewed him after seeing the movie), but definitely was not.

More harm than good?

One seemingly innocuous argument advanced by Treadwell opponents is that his good intentions did more harm than good; that by habituating the bears in Katmai National Park to friendly humans, he was making them more susceptible to poachers and other dangers. It's an argument used to try and sway those that might be more sympathetic to environmental concerns.

I believe, however, that the argument is somewhat of a red herring and not well supported by any evidence. All animals (including bears) habituate to infinite numbers of factors, behaviors and scenarios and their perception is far more advanced than, "I smell a human. It must be friendly." Just like many dogs can seemingly differentiate between someone coming to your front door with friendly intentions and a burglar coming to steal your stuff, bears can probably differentiate between hunters' behavior and the signature, friendly (albeit "unique") singing to them for which Treadwell was known. (As an aside and outside the scope of this point, the similarities which I saw between dogs and Halo Bay brown bears were rather surprising and amazing.)

It's also fairly commonly acknowledged that Treadwell dramatically overstated the threat of poaching in Katmai National Park, which--while perhaps detracting from his credibility--makes moot the argument about habituating the bears being bad for their well being.

Treadwell critics have also routinely cited poor food storage and eating habits (for those of you not well-versed in the etiquette of being in bear-country: it is generally advised that you either hang your food out of reach or store it in a bear-proof container and cook away from your campsite), which I also see as a bogus argument for two reasons:

- This Treadwell behavior is somewhat disputed. Those who knew him well have said that his campsite was usually in immaculate condition, so it's very possible that critics could have caught him on a bad day and unfairly generalized from there.

- More importantly, the brown bears of Halo Bay are decidedly not habituated to human food. Halo Bay is not Yellowstone. These bears do not associate humans with food handouts, they show little to no interest in human food, and the food that they have been eating for thousands of years such as sedge grass, berries, clams, puffin eggs, and salmon are extremely abundant. No matter what the National Parks Service tells you, visitors to Halo Bay routinely cook and eat in their campsites. Every bear viewing guide whom I met in Halo Bay cooked inside their campsites and one even admitted to cooking inside of his tent on rainy days and advised me that I was mostly welcome to do the same. I'm certainly not saying this to criticize Halo Bay visitors; I'm pointing it out to exonerate Treadwell from unfair criticism for doing things which are popularly believed to be safe and acceptable for this particular population of bears.

Perception of danger

So, when I take solo adventures into the wilderness, I generally take a lot of flack from family, friends, and loved ones whom have my safety in mind and want to see me come back in one piece (thank you for caring! :) ). When I return from my adventures, I unintentionally fluctuate back and forth between emphasizing the seemingly dangerous parts of my trip in order to give an interesting and exciting story and trying to assuage their fears that I may be less than one hundred percent safe. People are generally afraid of bears, so I took an order of magnitude more flack for this trip. This section constitutes my safety rant.

I had written on a facebook posting that visiting the bears was only potentially dangerous, not actually dangerous, but in retrospect I don't think that that adequately conveys what I'm trying to express. To use a driving analogy, I would maybe liken bear encounters with driving over the speed limit. You know that you are more than likely going to come away from the experience unscathed. But you may have some extra knowledge which makes you feel like you can handle it--at least in this particular situation (you've driven the road many times before / you have a good understanding of bear behavior and the way that you should act around them). You do have to have a heightened sense of awareness (watching more carefully for other cars on the road / paying close attention to the bears' stress levels and knowing when to give them space) and there are higher consequences of some unknown factor coming into play (a car pulling out in front of you / a bear being in an anti-social mood or feeling like you are threatening its food source). Those higher consequences (a high speed collision with another car / being swatted or attacked by a bear) are awesome enough--in the true sense of the word--that they are able to capture our imagination allowing irrational fear to override the actual probabilities of a problem.

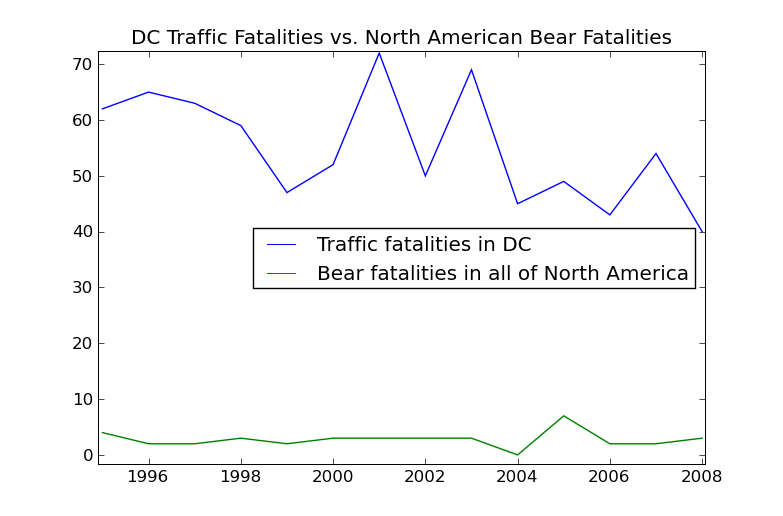

During the two months that I was away from Washington, DC a crazy 88 year

old gun-man assaulted innocent bystanders in the National Holocaust Museum

killing a guard and terrorizing everyone else. Nine people were killed and

over seventy people were injured in a train wreck on the same train line

(and in the same place) that I take home from work almost every

day. The number of people that died in Alaska due to bear attacks

during the time was exactly zero (in fact no one has died of a bear attack

in Alaska in the last four years). I put together a quick graph comparing

the traffic fatalities in DC vs. the known fatalities by bear in the

entire North American continent. The results are stark: I am

rightfully afraid to leave my house and commute to work every day. Keep in

mind that the resident population of DC and Alaska are approximately the

same at around 600,000 people.

While a true statistician could probably call "foul" here, my point is that people's perception of danger isn't based on actual danger or risk. Familiarity with things as mundane as driving (or in my case biking) to work leads to complacency and likewise lack of familiarity with things gives them the reputation as being dangerous, simply because people are irrationally scared of them. I believe that bears, like Treadwell, are very misunderstood by modern/post-modern North America. Sure they can kill you if you threaten them. But any number of humans can kill you, too, and for that we don't blame the entire human race; we blame the non-conforming individuals.

What I experienced in Halo Bay was an unspoken truce between the omnivorous coastal brown bears and the curious and fascinated people who went to visit them. In this in-tact ecosystem, food was plentiful and the bears were remarkably tolerant of visitors, clearly understanding that these people meant no harm to them. It felt almost utopian and an archetypal model of good human/nature interactions. I can very well understand what attracted Timothy Treadwell to this spot and what brought he and others back year after year after year. Hopefully, I will return myself some day.

blog comments powered by Disqus