NetCDF scale factors (and add offsets) explained Maximizing numeric range/minimizing storage

A little history

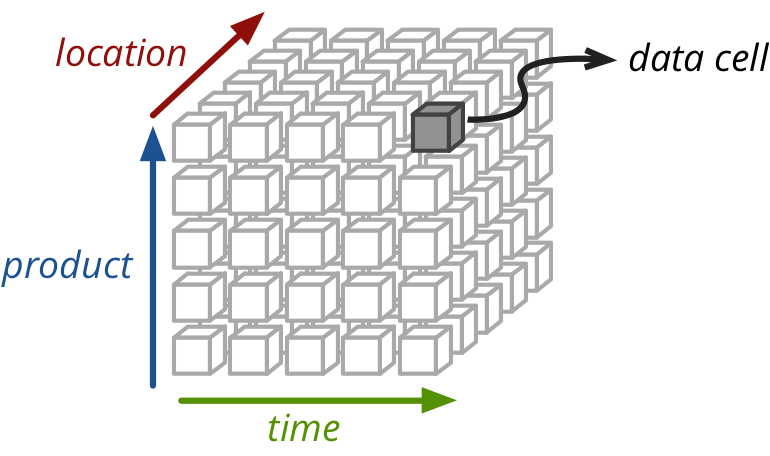

A number of years ago, waaaaaaay back in 2010, I was managing some output data from a hydrologic model (known as VIC). The 15 year old program had been written before spatial data formats and multidimensional data formats were common and/or invented, so its authors took a fairly naïve approach to data management. Simplified, the program took some weather input (temperature, precipitation wind) and calculated a handful of hydrologic output variables (soil moisture, baseflow, runoff). Conceptually, each of the input and output variables is multidimensional, typically 3, sometimes 4, and can be thought of as a data cube like the one shown below, but with X, Y and time axes.

The problem

VIC’s data management was such that it stored a single series of numbers in one file for each point in the product of the X and Y dimensions. I.e. one file per “grid cell” per variable. Large spatial domains can contain hundreds of grid points in each dimension, (our input data for BC contains 200 * 400 grid cells) so this would mean tens of thousands of input and output files. This becomes untenable and unmanageable very quickly. Consider that we normally have on the order of a dozen or so output variables and we model dozens of scenarios (27 for our CMIP3 work). Hundreds of Xs by hundreds of Ys by tens of variables by tens of scenarios, means millions to 10s of millions of files.

It turns out that the number of files (or inodes) on a filesystem is limited to about the range, and our hydrologists quickly found the limit. Having millions of files on your filesystem also slows down any algorithms that require a traversal of all files on the system (e.g. nightly backups, find, etc.). This had to be fixed.

The “solution”

As I alluded to, there exist specialized data formats that are tailored for this type of regular, multidimensional array data, such that you can pack much of the data into a single file. NetCDF is the primary candidate though there are numerous others that offer similar features.

So, I wrote a simple, one-off script, to be used once-ish (haha), that packed all of these single grid-cell timeseries into a single NetCDF file. It was simply named vic2netcdf. It did what it needed to do and it solved a problem that many people had. Unfortunately, it was commandeered and bastardized by future VIC users without checking some key assumptions: the worst of which was the use of scale_factors and add_offset attributes.

Scale factors and the pack hack

Using scale factors and offsets are nothing more than a storage performance hack. If used properly in a numerical domain where your data has a limited range or precision, they can save you a lot of space. But if used improperly, at best, they make your data pipeline confusing, and at worst they cause programming errors, data corruption or loss of precision.

Why scale factors?

Let’s quickly go over some basics of computational storage, to help explain why they would be used. Numbers are generally represented in the computer as either integers or “floating point” numbers. For both, the range of values that can be represented is a function of the number of bits. For example if we had a 4 bit integer, we could represent different integers over some range (either 0 to 15 for unsigned integers or -7 to +8 for signed integers). The actual range of a standard signed 32-bit integer is -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647. Floating point numbers are a bit more complicated, but for the sake of simplicity imagine using scientific notation such as . The number is described by two parts: the mantissa (1.5) and the exponent (4). Floating point storage is similar but the two terms are in binary instead of decimal (with a few more complications and specifics). In any case, the range and precision that you can describe is a function of how many bits you have. For a 32-bit float, you can represent numbers as small as and as large as .

If you have ever taken a look at a physical, mercury thermometer, you may have noticed that temperature on earth does not get that cold or that hot. Likewise, the maximum amount of annual precipitation on BC is on the order of 7500 millimeters and we don’t really need any precision greater than 1 millimeter. So the basic building block containers that we have for storing data, 32-bit integers and 32-bit floating point numbers, contain an enormous amount of wasted space given the precision that we require in this particular domain. There aren’t many containers that are smaller, but we do have 16-bit “short” integers that take up half the space and 8-bit “chars” that require half of that.

The new problem becomes the fact that our data are not integers, and the range of our data (let’s say 0.0 to +7500.0 for precipitation and -100.0 to +100.0 for temperature) does not necessarily overlap or match up with the range of short integers (-32k to +32k-ish).

How to use scale factors

It’s actually quite simple to compute a well-packed float into a short int (or even an 8-bit byte) and maximize the represented range. The following is adapted from Unidata’s NetCDF Best Practices document.

Writing a packing/unpacking function requires three parameters: the max and min of the data, and , the number of bits into which you wish to pack (8 or 16). In Python:

def compute_scale_and_offset(min, max, n):

# stretch/compress data to the available packed range

scale_factor = (max - min) / (2 ** n - 1)

# translate the range to be symmetric about zero

add_offset = min + 2 ** (n - 1) * scale_factor

return (scale_factor, add_offset)

or in R:

compute.scale.and.offset <- function(minimum, maximum, n) {

# stretch/compress data to the available packed range

scale.factor <- (maximum - minimum) / (2 ** n - 1)

# translate the range to be symmetric about zero

add.offset <- minimum + 2 ** (n - 1) * scale.factor

c(scale.factor, add.offset)

}

You can see how this plays out with a temperature range of -100 to + 100, and packing it into an 8-bit byte.

james@basalt ~ $ python

Python 3.4.1 (default, Apr 5 2015, 17:22:54)

[GCC 4.8.3] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> scale_factor, add_offset = compute_scale_and_offset(-100, 100, 8)

>>> scale_factor, add_offset

(0.7843137254901961, 0.39215686274509665)

>>> -100 * scale_factor + add_offset

>>> from math import floor

>>> floor((-100 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

-128

>>> floor((100 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

127

Notice how the bottom of our temperature range (-100) maps to the bottom of the byte range (-128), and likewise for the top. Now, in this case we would likely want a higher precision, since approximately 1 temperature degree of precision is not sufficient. But it’s simple enough to apply the same principle, and reuse our existing function to use a 16-bit short integer.

>>> scale_factor, add_offset = compute_scale_and_offset(-100, 100, 16)

>>> floor((-100 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

-32768

>>> floor((100 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

32767

And we can do the same with precipitation:

>>> scale_factor, add_offset = compute_scale_and_offset(0, 7500, 16)

>>> floor((0 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

-32768

>>> floor((7500 - add_offset) / scale_factor)

32767

If we want to clean this up a little bit, and make sure that we always get our arithmetic correct, we should probably write a simple packing and unpacking function:

def pack_value(unpacked_value, scale_factor, add_offset):

return floor((unpacked_value - add_offset) / scale_factor)

def unpack_value(packed_value, scale_factor, add_offset):

return packed_value * scale_factor + add_offset

Back to vic2netcdf.r

Remember that “one time script” that I wrote oh so many years ago? Do you think that I actually did this in the script? Of course not! I was being “one time lazy” and just hard coded the scale factors and add offsets. Actually I could be a little more generous to myself. Whoever “designed” the VIC input binary files used certain scale factors (but no offsets) and for that “one time only” we decided that it was best to just copy the binary data directly, and attribute the files with the old scale factors.

The problem with this was two-fold.

- Much to my chagrin, everyone continued to use this code, and continued to naïvely use the same scale factors

- The scale factors / add offsets that had been previously selected are terrible! Take a look at the temperature and wind speed that are represented by their choice of offsets (0.01, 0.0):

>>> scale_factor, add_offset = 0.01, 0.0

>>> unpack_value(-32768, scale_factor, add_offset)

-327.68

>>> unpack_value(32767, scale_factor, add_offset)

327.67

So we’re representing an air temperature range that is below absolute zero (i.e. physically impossible) and above the boiling point of water. We don’t need to do that. The wind speeds that we are representing are around 3x the Beaufort Scale’s “hurricane force”. This is overkill. But they chose an even worse set of translation parameters for precipitation: 0.025 and 0.0.

>>> scale_factor, add_offset = 0.025, 0.0

>>> unpack_value(-32768, scale_factor, add_offset)

-819.2

>>> unpack_value(32767, scale_factor, add_offset)

819.1750000000001

First of all, precipitation can’t be negative, so we’re already wasting half of our range. Second of all, the units for this variable are in millimeters per day. 800 mm would be about 10x the amount of precipitation received by the wettest area of BC over the entire year. So again, this is a poor choice of scales. A better set of parameters might be:

>>> compute_scale_and_offset(0, 8000 / 365., 16)

(0.00033444431554403116, 10.959071331746813)

And you might even be able to get away with packing it into an 8-bit char.

>>> compute_scale_and_offset(0, 8000 / 365., 8)

(0.085952189094816, 11.001880204136448)

Conclusions

Packing floating point numbers into smaller data types has the potential to half or quarter the data input or output requirements for an application. It’s easy to get the scaling parameters wrong, and most of the ones that we use at PCIC are inappropriate. The code to compute the correct parameters is fairly trivial. The down side is that it complicates your code and your processing chain, and you have to make absolutely sure that any file I/O checks and uses your scale factor and add offset. Some NetCDF libraries/applications will do this for you and others will not. Make sure that you know which you are using.

I hope that this has been helpful to any readers, especially those who have been stuck with using the ancient vic2netcdf.

Thanks to Arelia Werner and Mike Fischer for reviewing ealier drafts of this post.

blog comments powered by Disqus